Dr Katie Knight | Dr Sandra Subtil

Thought you’d left hypertensive patients behind when you chose paediatrics? There may be a lot less of them, but that means many of us feel a tad rusty when it comes to assessing and treating our young patients with high blood pressure.

First, definitions (and some nerdy history).

While adult hypertension is defined by the morbidity and mortality associated with a certain level of BP, in children ‘hypertension’ is a more arbitrary value, based on the normal distribution of BP in healthy children.

The first set of ‘normal range’ children’s blood pressures was published back in 1977, but these were immediately controversial as they seemed to

give numbers that were way too high, based on paediatricians’ experiences with real patients. Soon, height percentiles were included in the tables as well as age and sex, which made it a bit more accurate… but also harder to interpret.

The mildly intimidating sounding ‘Task Force on BP Control in Children’ later updated the normal ranges, based on measurements from over 70,000 children, and defined hypertension as average systolic and / or diastolic pressures persistently above the 95th centile, with SEVERE hypertension defined as above the 99th centile.

This table simplifies the categories of hypertension by centiles:

| Blood pressure category | 0-15 years: systolic BP centile | 16+ years: systolic BP |

| Normal | <90th | <130/85 |

| High normal | >90th to <95th | 130-139/85-89 |

| Hypertension | >95th | >140/90 |

| Stage 1 hypertension | 95th to 99th plus 5mmHg | 140-159/90-99 |

| Stage 2 hypertension | >99th plus 5mmHg | 160-179/100-109 |

| Isolated systolic hypertension | Systolic >95th, diastolic <90th | >140/<90 |

And you can find full BP centile charts here.

Primary (‘essential’) hypertension is becoming more common as childhood obesity is increasing.

Secondary hypertension is when there in an underlying cause – usually renal, cardiovascular or endocrine. The higher the BP is above normal, the more likely there is an underlying cause, and if there are end organ complications, this should definitely be making you suspicious. Also- the younger the child, the more you should suspect underlying disease (the most common would be renal/renovascular disease).

A Hypertensive CRISIS is severely elevated BP plus any evidence of end organ injury for instance papilloedema, rising liver function tests, left ventricular hypertrophy, hypertensive encephalopathy

Hypertensive URGENCY means elevated BP above the 95th centile but no evidence of secondary organ damage. However… if left untreated, end organ injury could happen at any time.

Hypertension that is asymptomatic still needs attention. As many as 30-40% of young people with primary hypertension will have a large left ventricle (10-15% of these will have severe left ventricular hypertrophy) but with the right treatment this can actually resolve. In young people with chronic kidney disease (CKD), strictly controlling the BP decreases proteinuria and slows down the process of CKD.

Numbers

Are you ready for this?

The automatic (oscillometric) BP cuffs we use all day every day… ARE LYING TO US.

There are so many variables –the cuff size, different algorithms used in different machines, how cross / playful / wild the child is at the moment the blood pressure measurement is taken – that the reading on the screen is NOT likely to represent what the blood pressure actually is. And remember, the blood pressure centile charts we use were made based on MANUAL, not automated blood pressures!

Unless you are in PICU and the child handily has an arterial line, the only way to get a ‘proper’ BP reading is with a calm child (get the play specialist to help), a manually inflated cuff, and a Doppler probe on a distal artery. Guaranteed to impress the nephrologist if you do this before calling them!

Even manual readings should always be repeated more than once, and hypertension treatment should NEVER be started based on automatic BP readings.

Here it is demonstrated on an adult patient (just a big child, right?) same principle applies with a child only with more bubbles / stickers / persuasion.

The clinical history

Your standard paediatric history should include a few other important details. Keep in mind you are searching for an underlying cause, as well as looking for evidence of target organ damage.

- Were they very unwell in the neonatal period – did they need umbilical arterial or venous lines? Invasive central lines can cause trauma to the large vessels could have affected the blood flow to the kidneys, leading to high blood pressure.

- Is there a history of recurrent urine infections? Repeated infections (especially if they have developed into pyelonephritis) can damage the kidneys

- Polyuria or polydipsia, suggesting diabetes?

- Family history of high blood pressure, or any endocrine disorders; any deaths related to cardiovascular disease?

- Drugs – steroids (maybe recurrent steroid courses in badly controlled asthma); if your patient is a teenage girl are they on the contraceptive pill?

- Social history – any illegal drug use? Cocaine and amphetamines cause hypertension.

- Lifestyle – diet and activity level, calorie intake – what is the BMI? Work out salt intake– look at the sodium content on food labels, and times it by 2.5. (e.g. 2.4g sodium = 6g salt).

Recommended salt intake

1 to 3 years – 2g salt a day (0.8g sodium)

4 to 6 years – 3g salt a day (1.2g sodium)

7 to 10 years – 5g salt a day (2g sodium)

11 years and over – 6g salt a day (2.4g sodium)

- Symptoms suggesting hypertensive crisis – like persistent headache, vomiting, confusion (i.e. hypertensive encephalopathy), epistaxis, abdominal pain

Examination

There are (probably literally) 101 possible causes of hypertension. The common causes by age group (see table below) are helpful to keep in mind, but there quite a few more unusual underlying diagnoses. Many of the rarer causes have clinical signs that are worth hunting out to piece the puzzle together.

Before the examination make sure you start with a full set of vital signs, including 4 limb BPs (yep you guessed it, done manually with Doppler probe if you can). You’ll need an accurate weight and height as well to be able to use the BP centiles charts.

So from top to toe…

- HEAD

Neurological examination, including mental state (think hypertensive encephalopathy) and fundoscopy. Any sign of head trauma, recent head injury? Think about NAI…

- NECK

Thyroid examination (hyperthyroidism?), throat examination. Large tonsils and history of snoring? High BP could be linked to obstructive sleep apnoea

- CHEST

Heart sounds, heart rate, pulses (especially femoral pulses – you could pick up signs of a coarctation). Any signs of heart failure, pulmonary oedema, ventricular hypertrophy? Systolic murmur could be another sign of coarctation of the aorta, tachycardia might make you consider hyperthyroidism, or rarer things like phaeochromocytoma

- ABDOMEN

Palpate for masses (Wilms tumour, polycystic kidneys, neuroblastoma etc) and listen for renal artery bruits that you might hear in renal artery stenosis. Is there hepatomegaly that could point to heart failure?

- GENITALIA

Ambiguous genitalia or virilisation – think adrenal hyperplasia

- SKIN

A few signs linked to conditions worth mentioning:

- Pallor, flushing or diaphoresis – phaeochromocytoma

- Acne, striae – Cushing’s syndrome

- Café-au-lait spots – Neurofibromatosis (linked with renal artery stenosis)

- Adenoma sebaceum – tuberous sclerosis (linked with renal cysts and renal angiomyolipomas)

- Malar rash – SLE (i.e lupus nephritis / glomerulonephritis)

- Acanthosis nigricans – type 2 diabetes

Investigate…

All hypertensive children should have these tests ordered: urine dipstick and culture; FBC, TFT, U&Es; Abdomen/renal USS; echocardiography, fundoscopy

In obese children (and those with diabetes or chronic kidney disease) – add a lipid profile, fasting glucose, and a urine albumin-creatinine ratio.

Drop The Pressure

The goals of treating hypertension are:

Lower the blood pressure to within normal range – but be safe and effective.

Recognise any secondary consequences of the hypertension, and deal with these too

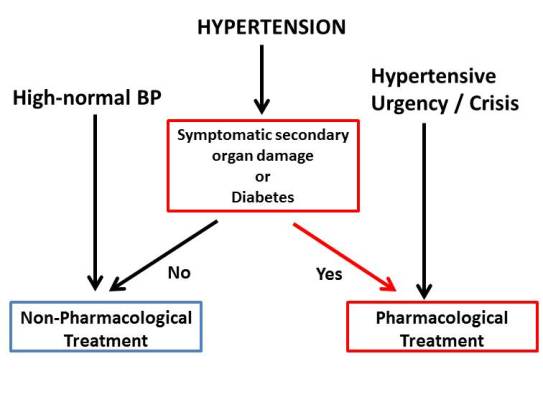

Non-pharmalogical treatment includes lifestyle advice (diet, exercise, reducing salt intake, reducing BMI).

In a hypertensive CRISIS (i.e. where there is evidence of end organ damage) the BP has to

be immediately brought down to an appropriate level. Aiming for 25% of the planned drop in pressure in the first 6-8 hours, and the rest over 24-48 hours, is sensible. The last thing you want to do is to drop the blood pressure too quickly – if there is a sudden fall in blood flow to end organs this can cause ischaemia and infarction (eeek).

In hypertensive URGENCY, BP can be lowered more gradually, over 24-48 hours.

The fact that these children are so vulnerable while their blood pressure is brought under control means that generally they will be treated in intensive care.

Help, I did adult medicine ages ago and can’t remember any antihypertensives

Don’t panic, this is not a decision for you to make alone (or actually for you to make at all). The choice of which antihypertensive to use must be made in conversation with your friendly cardiologist and/or nephrologist. The drug they choose will depend on the side effect profile and the underlying likely cause of hypertension – but most importantly it should drop the blood pressure safely (i.e. slowly) and effectively.

In Summary

If you want an accurate BP reading, use a manual cuff and Doppler probe

Don’t forget to consider rarer endocrine causes of hypertension and look for clinical signs as clues

Aim to lower the blood pressure safely, and only following the advice of cardiology and renal teams

References / Further Reading

How to Define Hypertension in Children and Adolescents

Clinical overview of hypertensive crisis in children

15 min consultation: the child with systemic arterial hypertension. Sing et al, ADC 2017